Taubes-Guyenet debate. My analysis (III)

(Versión en español: hacer click aquí)

My notes on the 3rd segment of the debate and my comments below them:

- [SG 1h2m] When you use accurate methods you find that people with magical metabolism, those who have obesity and don’t eat very much, seem to not exist any more.

- [SG 1h3m] I want to talk about studies where they increase calorie intake. If we want to understand why people get fat, we can look at studies that overfed people on fat or carbohydrates exclusively. In one study they calculated the energy requirements and then they increased that by 50% with fat or carbohydrate. This is Horton’s study, reference [16]

- [SG 1h4m] If Gary’s hypothesis is correct, these people should have gained fat in the carbohydrate overfeeding but not the fat overfeeding. These people were in a metabolic ward, so the researchers could monitor everything. No cheating. No inaccuracy.

- [SG 1h6m] What they found is that at the end of a 2-week period of overfeeding, the carb and fat group gained exactly the same amount of body fat. In a 2nd study they did the same thing and found the same result. 3-week-long experiment. Different insulin responses, different amounts of carbohydrate and fat, exact same amount of fat gain. This demonstrates that insulin is not what gets fat into fat tissue. Calorie intake is what controls that.

- [GT 1h7m] The paradigm you work in determines the questions you ask. This experiment assumes people get fat by overfeeding. They think they are just doing what happens naturally. They are answering the question of whether people can get fat by overfeeding. This experiment is built on the paradigm they want to test.

- [GT 1h7m] [Comments about the relationship of Peters JC, Hill JO. with Olestra and the sugar industry]

- [GT 1h10m] 10 kcal/d, less than a bite of food, explains obesity. How do we explain those 10 kcal/d? Is the brain somehow regulating that? Or is it due to a disregulation in the body that traps fat in the fat cells or prevents fat from being used for fuel? If someone drinks 5 beers a day, may be he/she only stores 10-20 kcal/d, how does that happen and why does it go here and not there?

- [GT 1h12m] It is not that hard to imagine that someone during a relative famine can store 10 kcal/d. If they are only eating 1200, 10 get stuck in the fat cells and 1190 are excreted or expended. Nothing in the laws of physics says so. In animal models you can disassociate obesity from eating too much.

- [Joe Rogan] In essence you’re saying that even if someone is consuming a lot or a few calories each day, 2000 kcal/d, if those calories are consumed in the form of sugar, the body will store part of them, even if the body is not receiving enough food, while if you consume protein, vegetables, etc. your body will not do that.

- [GT 1h13m] This brings us to the subject of evidence and mechanism.

- [Joe Rogan] But you’re saying that, right? If two people follow the same caloric intake, one of them with 2000 kcal/d of chicken, fish, vegetables, and the other one of 2000 kcal/d of milkshakes and sugary drinks, pasta and BS, that person is going to gain a certain amount of calories and put them to fat, regardless [of calories].

- [GT 1h14m] Yes, that is the hypothesis. And that hypothesis can be tested. Stephan thinks it has been tested 80 times, I think they have done a bad job of testing it. And we both tend to reject the studies that we do not like, when we define «don’t like» as not having the answer that we think is correct.

- [Joe Rogan] But You, Stephan, you think that this is not correct. You say that in the study where they add additional fat and additional carbohydrates, they both gain the same amount of weight.

- [SG 1h14m] That’s right. If Gary’s hypothesis is correct, you have to see different levels of fat gain.

- [Joe Rogan] It was a short term study?

- [SG 1h14m] Yeah, it was a short-term study. 2 and 3 weeks. It is very short. But if insulin is the hormone that puts fat into fat cells, you should see any kind of difference, some kind of effect on fat gain.

- [GT 1h15m] One problem with overfeeding studies is that one of the hypothesis says energy balance is dependent on the macronutrient content of the food. Therefore you are going to have different levels depending on what the macronutrient content is.

- [GT 1h16m] Ludwig’s study is an example. They saw different levels of energy expenditure depending on the carbohydrate content of the diet. The lower the carbohydrate the higher the energy expenditure.

- [GT 1h18m] Experiments should take into account all the competing hypothesis. If there is a threshold effect of insulin, which actually there is, you don’t actually expect to see any difference between groups, since they are both in the plateau of the insulin response. If it actually is activated in both groups, both hypothesis predict the same fat gain.

- [GT 1h20m] Anecdote about an obese friend. My hypothesis is that he would have gained weight regardless of eating or not 300 kcal extra a day, because his insulin was elevated.

- [SG 1h20m ] It is easy to tell stories, it is not easy to tell stories that are supported by scientific evidence.

- [SG 1h20m ] 29 studies have measured energy expenditure on diets differing on carbohydrates and fat content. When you put all these studies together, it makes almost no difference in the metabolic rate if people are eating carbohydrates or fat. In fact, the very small difference favors high-carbohydrate diets.

- [SG 1h21m] The study Gary says (Ludwig’s) is the one that reports the biggest difference among those 28+1 studies.

- [SG 1h22m] In Ludwig’s study, some of the participant’s data are literally physically impossible. If you remove the clearly erroneous data, the study no longer reports a higher energy expenditure on a low-carbohydrate diet and is consistent with the previous 28 studies.

- [SG 1h23m ] In regards of the 10 kcal/d, Gary, I continue to have the feeling that you don’t understand human energetics, because that is not how it works.

- [GT 1h23m] You are insulting me, you have to stop doing that. You keep acting as if you think I am an idiot.

- [SG 1h23m] It only takes a small amount of extra calories to make someone gain fat. As they get fat their calorie needs go up.

- [GT 1h24m] How does the brain do that?

- [SG 1h24m] I didn’t say the brain does that. The point is that by the time they have obesity, they are consuming 20-35% more calories than they were when they were lean. It is not one of 2 cokes a day that is allowing them to remain obese, they are consuming 20-35% more. It’s not 10 extra calories.

- [SG 1h26m] If you eat 10 kcal more than you need, you store them.

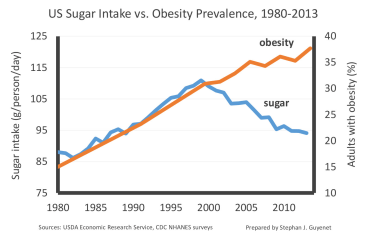

- [SG 1h27m] Sugar intake has been declining in the USA during the last 20 years, it peaked in 1999 and it is now 15-23% lower than it was in 1999. Obesity has increased during the last 20 years. The same in the UK.

- [SG 1h29m] Taubes counterargument is that the amount of sugar we consumed 20 years ago may influence us today.

Arrogance is not the same as assertiveness

In this segment we have Guyenet again qualifying Taubes’ opinions as story-telling, presuming to defend an opinion based on scientific evidence and stating that his interlocutor does not understand the energetics of the human body. I insist on the warning that we should not take Guyenet’s arrogance as a symptom that he is right or that he knows what he is talking about. Arrogance is only a sign of arrogance, nothing else. And do not mistake arrogance for assertiveness.

Guyenet disinforms about sugar

I start with the end of the debate segment. Guyenet cites at 1h27m the fact that, in the USA and in the UK, the rate of obesity continues to rise although sugar consumption has been declining in the last decades. The argument is inappropriate for a person with a college degree, specially if this person has a PhD. It doesn’t matter how arrogant he is: his argument is unquestionably stupid.

Why is it stupid? It is explained in these two articles:

- Guyenet refutes the idea that sugar causes obesity

- If your sugar intake today is lower than yesterday’s, do you slim down?

In the following graph I show the annual sugar intake in the USA (blue curve) from 1980 to 2015 and the annual increment in the percentage of obese adults (orange curve):

As we see, there could be a causal relationship between sugar consumption and body weight, since changes in sugar consumption correlate with the growth rate of obesity. When the consumption of sugar goes up, obesity grows faster. And there is also a good correlation in the case of sugar-sweetened beverages. This is not proof of a cause-and-effect relationship, but a cause-effect relationship can’t be ruled out with these data.

Well, Guyenet, who has a Ph.D., assumes that if sugar is fattening there must be a direct relationship between sugar consumption (blue curve) and the integral of the orange curve (i.e. the accumulated value), something that does not make any sense when assuming that sugar is fattening, which is the hypothesis that he wants to refute. If he had just represented the data in another way, as we have seen in the graph above, he would have found that direct relationship that he believes does not exist.

And since he doesn’t find a direct relationship where nobody expects it to be, he assumes that sugar cannot be an important factor in the obesity epidemic. Regardless of whether this is true or not, regardless of the relevance of sugar in the obesity epidemic, Guyenet’s argument is blatantly wrong. For more detailed explanations of Guyenet’s mistake, I refer to the two blog posts (English language in both of them) I linked above.

Let’s not mistake arrogance for competence.

False dichotomy fallacy

[SG 1h6m] This demonstrates that insulin is not what gets fat into fat tissue. Calorie intake is what controls that.

Even if Guyenet were right about insulin, it doesn’t follow that calorie intake controls fat accumulation. He is using the false dichotomy fallacy. His claim that calorie intake is what controls body fat accumulation has to be proved.

Taubes’ arguments

Some of Taubes’ arguments seem remarkable to me:

- 10 kcal/d, which is less than a mouthful of food, explains obesity. How do we explain those 10 kcal/d?

- It is not so difficult to imagine that someone during a relative famine can store 10 kcal/d. If they are only eating 1200 kcal/d, 10 remain in the fat cells and 1190 are excreted or spent.

- In animal models one can find the dissociation between obesity and eating too much.

Guyenet avoids addressing the first argument, as I explain below. Guyenet says that eating too little you cannot get fat, as we saw in part II of my analysis. In regards of the third one, and this is something we have seen in this blog, experiments with animals do show that they can gain body fat without an increased intake. How can Guyenet explain his irrational belief that overeating is a requirement for weight gain in humans?

Overconsumption experiments

This is one of the most interesting parts of the debate. Guyenet begins by citing the overconsumption experiment by Horton et al. 1995 in which extra food is given in the form of fat or in the form of carbohydrates. And Guyenet says, literally, that if the carbohydrate-insulin hypothesis were correct, differences between both diets should have come up, and he says that fat gain was the same in both groups.

We have already commented this experiment in the blog (see). Let’s watch again the graph of the fat balance (difference between ingested and oxidized fat) from this study:

As we can see, the first few days the 50% extra calories that are consumed as fat (black dots) are more fattening than when given in the form of carbohydrates (white dots). The two diets do not produce the same outcome, in contrast with what Guyenet says. This is very important, because anyone who hasn’t read this article and listens to Guyenet’s claims, is being deceived. Extra dietary fat makes you fatter than extra carbohydrates, at least in the two weeks of this experiment. And this is clearly stated by the authors of the experiment:

we find that for equivalent amounts of excessive energy, fat produces more accumulation of body fat than carbohydrates.

This is an inconvenient truth for Guyenet’s claims. And he hides this fact. He says that according to the carbohydrate-insulin hypothesis there should have been a difference between groups, and he says there is not. But the truth is that there are differences between groups, differences that refute Guyenet’s hypothesis, which is that the accumulation of body fat is determined by the caloric intake.

This demonstrates that insulin is not what gets fat into fat tissue. Calorie intake is what controls that. Stephan Guyenet, PhD

Guyenet uses this experiment as a refutation of Taubes’ hypothesis, but he hides that the experiment refutes his own hypothesis. It is not the calories in the diet what determines the accumulation of body fat. This experiment is very clear about this.

If we want to understand why people get fat, we can look at studies that overfed people […]

As I said, this is a very interesting part of the debate. And there are many clarifications I want to make. For example, that this type of experiments do not demonstrate that we gain fat because we eat more than we expend, which is Guyenet’s hypothesis. The overeating hypothesis is very complicated to test. How would it be tested? Imagine that we have two groups of participants to whom we give exactly the same food, but each day we give 10 kcal/d extra to one of the groups. As one group gets fatter than the other –if that actually happens— the intake would be adjusted to continue giving those 10 extra kcal/d that make them gain body fat. And, after 5 years, for example, that group would have gained 2.5 kg more than the other group, if the overeating hypothesis is correct. Of course, the experiment would have to be done with all kinds of diets, since checking the result only in one diet would not guarantee the same outcome with a different diet. I assume everybody can see the difficulty of carrying out this experiment with enough participants, for enough time, with enough control of the intake, testing a wide-enough set of diets and with enough control of the levels of physical activity to test this hypothesis. As the test cannot be performed under real conditions, what the overeating experiments do is change the conditions to achieve a much greater effect and much earlier. The experiment that Guyenet cites does something completely different from the situation of interest: they give 1000 or 1500 extra kcal/d each day on top of a specific diet, and, they assume that if that causes body fat accumulation, the mechanism by which people who do not force theirself to eat those extra 1000 kcal/d is the same as in that experiment, regardless of the diet composition. That approach is called the fallacy of a single cause, which is to suppose that when a cause of an effect has been found, that one is the only possible cause for that effect. The reason why a person gets fat when they are not forced to eat exorbitant amounts of food day after day may not have to do with the amount of food, but with its composition. That idea is what Taubes proposes. But that possibility is discarded without any further explanation by the advocates of the energy balance pseudoscience, like Guyenet. We can also interpret this error as a fallacy of continuum: although we do not know at which moment we are going to begin to gain weight «because of the excess» when we progressively increase the amount of food, something that will happen if you force yourself to eat much more than a normal person does, it does not follow that food ingestion in normal amounts and an abnormally high food intake are comparable situations. And these experiments claim that both situations are the same and aim to shed light on how obesity develops. And, as a matter of fact that is the way Guyenet introduces them: «if we want to understand why people get fat, we can look at studies that overfed people».

The overeating experiments are the ones that can be done, and the ones that researchers can include in their CVs, but not necessarily those that bring light on the nature of obesity. Note, on the other hand, that those experiments do not test Taubes’ hypothesis: they do not change the composition of the food in order to produce a bigger or smaller insulin secretion. As Taubes says, these experiments assume that they are testing what happens naturally in the person who gains body fat. It is not necessarily true. They show that ONE WAY to gain body fat is to force an extreme food intake. One way, not necessarily the only one. This experiments do not show that this is the way in which those of us who do not force ourselves to eat exorbitant amounts of food gain weight.

Note from this experiment we only have fasting insulin data, not postprandial levels. Therefore, it is not possible to talk about relationships between fat accumulation and insulin levels. Guyenet assumes that for the high-carbohydrate extra load the secretion of insulin will be greater than for the high-fat extra load, but he does not know if it is true because that data is not in the article.

Another important aspect of this experiment is the time evolution of the outcome. At the very first days, the extra dietary load in the form of fat is more fattening than the dietary load in the form of carbohydrates, but as the days go by, the oxidation of fat is reduced in the high-carbohydrate-load diet, and after 14 days the two diets are almost equally fattening. What happens in the longer term? It is not tested, and we cannot make it up. In these unreal conditions, in the very short term, we know what happens, but in the long term we don’t know what will happen. We cannot draw conclusions about the effects of a diet from short-duration experiments, even if these experiments are the ones that can perform the best measures (see), because what they measure is irrelevant. The relevant outcome is the effect of a diet when it is followed for years.

Guyenet cites another overfeeding experiment (see), which, when examined in detail, doesn’t seem to prove anything. I analyzed it in a separate post, so the length of the present one was not increased. I just point out that the results in terms of body fat accumulation in that experiment are very unreliable and that Guyenet argues that there are different insulin responses in that experiment, when the authors actually said «no significant differences». Another inconvenient fact that Guyenet misrepresents.

Hall and Guo’s meta-analysis

Guyenet mentions a meta-analysis by Hall and Guo that concludes that for any practical purpose, a calorie is a calorie.

In other words, for any practical purpose «a calorie is a calorie» when it comes to differences in body fat and energy expenditure between controlled isocaloric diets that differ in the ratio of carbohydrates to fat. Hall and Guo .

We have also seen that meta-analysis in the blog (see). As we have just seen, the effect of a diet changes over time, so I represented the duration of the experiments with the effect on body fat. As we see in the following graph, most of the experiments included in the meta-analysis are less than two weeks long, practically all of them reporting less accumulation of body fat with the diets that have more carbohydrates and less fat:

But, as we see in the graph above, for the experiments of greater duration (around a month and a half) the result is favorable in general to the diets that have less carbohydrates.

Hall and Guo don’t take into account the duration of the experiments, they put all together in a meta-analysis and they conclude that there is not a clear winner, so there is no effect of the diet composition! Well, that’s wrong, the composition does matter. If you follow the Western standard diet, with 50-60% carbohydrates, a sudden increase of dietary fat can cause you to accumulate body fat during the first days after the diet change, an effect that is biiger than if you increase carbohydrates and reduce fat. The composition of the diet does matter. But if you follow a diet for two months, it may be the other way around. If you have the «practical purpose» of living more than two months, this meta-analysis does not rule out the importance of the diet composition. We don’t know what happens in the long term and we can’t make it up.

Again, let’s notice that Guyenet says that this meta-analysis finds no differences between diets: it’s not true, and anyone who listens to him is being deceived. But to say the truth is inconvenient for the pseudoscience he defends. There are differences between diets and that fact refutes his hypothesis that body fat is determined by the calories in the diet . You always have to check the data and trust no one.

Ludwig’s experiment

This experiment is commented in this blog post, and one of the authors describes it here.

What happened with this experiment? The first reaction was to try to discredit the study by stating that the way of calculating the results had changed, because the outcome was not what the researchers wanted.

Is that true? According to David Ludwig (see), the protocol of the experiment was unusually detailed (unlike other experiments, in which the authors don’t give many details and then they do whatever they fancy) and was incorrectly stated. As the experiment progressed, they were fixing mistakes. And, when they realized that the measure of the energy expenditure was wrongly specified: they fixed the mistake. This happened BEFORE BREAKING THE BLIND in the experiment. I say this again: they fixed the mistake before breaking the blind.

The error was recognized and corrected a priori. We obtained IRB approval for our final analysis plan on 06 Sept 2017, before the blind was broken (and indeed, before measurement of the primary outcome had been completed by our collaborator Bill Wong in Houston). Similarly, we corrected the Clinical Trials registry prior to breaking the blind. We provide documentation of this timeline, and additional detail, in the Supplement Protocol section.

This is important: they fixed the error in the protocol without knowing if that correction would benefit one outcome or another. Therefore, to affirm that the protocol was changed because the data did not reflect what they wanted, is defamation. But, of course, the outcome of this experiment was inconvenient for Hall, Guyenet and their friends.

What has Hall done? With the unblinded data, which was provided by the authors of the experiment, he has looked for alternative ways to calculate an outcome so the statistical significance is reduced (see). For example, calculating the effect of different diets not from the moment they start to be different, but from before that, introducing noise in the measure:

I refer the interested reader to Petro’s analysis of Hall’s Hall’s jiggery-pokery:

|

|

Moreover, Guyenet says that there is dietary intake data for some participants that would violate the first law of thermodynamics, and that if the data from those participants is removed from the calculations the differences between diets disappear. This is not true. In this experiment we have both energy expenditure data and energy intake data, the latter being used as a corroboration of the former, since it is a fact that dietary intake data are inherently unreliable. As I understand it, Kevin Hall (see) decided to redo the analysis of the data by discarding the energy expenditure data of those participants whose energy intake data he thought was erroneous, a very questionable decision, since an error in the energy intake does not invalidate the corresponding energy expenditure data, which may still be correct. Even if the energy intake data is incorrect, the corresponding energy expenditure data is from of a person who maintains their body weight, and that’s what the experiment was about. By making that very debatable —-and convenient for him— reanalysis of the data, as the threshold for data elimination was lowered, the difference between groups was reduced, but the difference between groups was not eliminated as Guyenet claimed in the debate. In Hall’s words:

The intercept of the best fit line was 30 ± 3 kcal/d per 10% reduction in dietary carbohydrates and corresponds to the estimated dietary effect on TEE when all energy is accounted

A TEE increment by 30 kcal/d for every 10% reduction in the percentage of carbohydrates is a huge amount. An effect of that size can perfectly explain the difference between regaining the lost weight and keeping the lost weight. The difference between diets has not disappeared, it has only been reduced by this more than questionable data manipulation by Kevin Hall. Guyenet’s claim that there was no difference between diets is a lie.

It is Hall who has performed an alternative analysis of the data because the outcome of this experiment is inconvenient for the hypotheses on which he has based his career. And he has used unblinded data, knowing exactly what he had to change to achieve the desired result. Accuse the other side of what you are guilty.

Remember these actions by Hall and Guyenet, because later in the debate Guyenet will accuse Taubes of saying that experiments are garbage when they do not support his beliefs:

There is a remarkable correlation between studies undermining your beliefs and you thinking about those studies as garbage. Stephan Guyenet, PhD

Does he talk about Taubes or is he talking about Hall and himself? Huge hypocrisy!

10 kcal/d

Finally, we have the Guyenet’s insult to Taubes, saying that, in his opinion, he doesn’t understand human energetics (n.b. I didn’t know that there are special energetics for humans). Taubes asked him to stop treating him like he was an idiot. And Guyenet’s insult precedes him telling something that everyone knows, which is that when you get fat you usually have an increased energy intake and an increased energy expenditure. Is that what Taubes doesn’t understand? What a clarification from this energy genius named Guyenet.

But let’s not lose sight of Guyenet’s maneuver: as he cannot talk about «excess» in a person who accumulates 10 kcal/d and has still not gained weight, what he does to avoid explaining that situation is to talk about a situation that has nothing to do with it, which is that of a person who is already obese. Then he defines «excess» as the difference between what that person eats and what a lean person eats. He says that people do not lose weight because they eat more than lean people. That is his belief, but he doesn’t know if it’s because of that or it isn’t. This is just his baseless belief. But he has avoided talking about the fattening process and has made it clear that, in his opinion, if you are overweight, you eat too much and that’s why you don’t lose your extra weight. This is a good trick, but the only thing that shows is his inability to answer Taubes question.

Taubes understands what Guyenet is explaining, but he doesn’t believe that body fat gain is caused by too much energy. And he believes that it is possible to gain weight without an increased intake, something that Guyenet believes is a requirement to gain weight. Guyenet insults him but he is not able to explain why Taubes’ view is wrong.

Go to the conclusions

Go to the fifth part

Go to the fourth part

Go to the third part

Go to the second part

Go to the first part

Hall is the definition of bias:

Puede que haya algo de satisfacción en pinchar las afirmaciones que hacen los campeones low-carb sobre la superioridad metabólica.

Debacle or debate?